A bomb threat was submitted by either a Chinese Communist Party functionary or by a fan of the Party, one of the blokes whom Chatham House calls “semi-private enforcers.” The threat succeeded in delaying a showing of “State Organs” at a venue in Australia.

A report on the incident oddly describes “State Organs” as a film that “purports to investigate allegations that the Chinese government has been systematically harvesting organs from prisoners of conscience, including Falun Gong practitioners, Uyghurs, and other detained groups.” The author must know enough to know that the film does not merely purport to inquire.

Low and high

Chatham House’s Jennifer Lind observes that the CCP’s resort to markets, by enabling a massive expansion of its resources and capacities, “has upended ideas about autocracies’ limitations” (November 27, 2025).

The CCP also tolerated a bounded form of pluralism: allowing a thriving private sector, a vast private media, and increasingly well-regarded universities—even as these spaces remained under party oversight. This government-managed civil society has allowed the exchange and diffusion of ideas. And, as Jessica Teets observes, it has helped the CCP identify pressing societal problems and negotiate policy reforms.

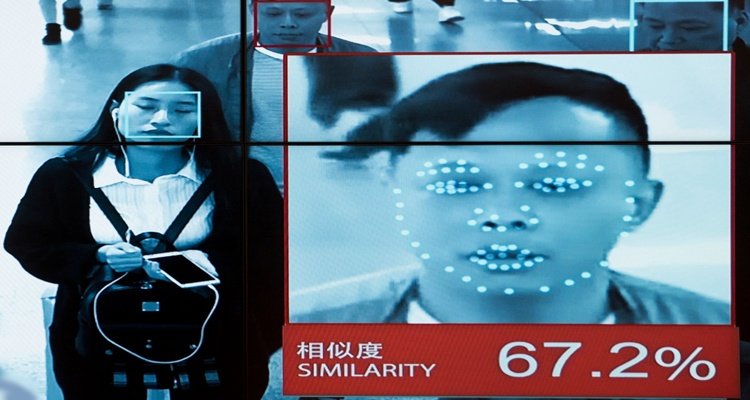

Smart authoritarians created ways of controlling information far beyond mere censorship. Rather than blanket bans, the CCP employs what Margaret Roberts terms ‘friction’ and ‘flooding’: subtle tactics that delay access, drown dissenting views and desensitize the public to pervasive state control.

Over time, the CCP also shifted from high- to low-intensity repression, adopting selective and pre-emptive coercion in place of overt violence. Furthermore, as Lynette Ong has shown, the party relies on semi-private enforcers to distance itself from intimidation and violence. With the rise of artificial intelligence, facial recognition, and other biometric surveillance, the CCP increasingly maintains its grip through algorithms rather than force….

The US and other liberal countries must coordinate how to respond to the rise of an authoritarian superpower. Washington could not contain a superpower on its own during the Cold War and it cannot now.

The reference to grip-maintaining by “algorithms rather than force” is imprecise. The algorithms are a means of coercion. Also, as works like “State Organs” attest, “low-intensity repression” doesn’t cover the waterfront of how the Party has conducted itself in recent decades. All the low-intensity repression paves the way to a lot of high-intensity repression.

China’s post-Mao turn to a more fascist version of totalitarianism—one that commentators concerned to be kinder and gentler call “authoritarianism”—has indeed enabled the state to acquire wealth and knowledge that it uses to advance its totalitarian ambitions. But that it condescends to allow a substantial amount of market activity does not mean that the Chinese Communist Party’s oversight and control, which it endeavors to exercise over everything—the total—has receded.

In modern China, businessmen have a chance to accumulate capital and innovators have a chance to innovate, but always within strict limits and always subject to the state’s continuous censorship, surveillance, direction, and sudden interference. Many other governments exercise the same routine coercion. One of the things that makes the Chinese government different, in addition to the size of the country it governs, is the pervasiveness of its overlordship, further expansions or intensifications of which are always being announced.

Near and far

The Party’s omni-tentacled efforts to impose its will range way beyond the large territory and population of China.

Such efforts include constant pressure in the Taiwan Strait, the South China Sea, and other waters and border regions; and harassment and even kidnapping of expatriate Chinese nationals and others almost wherever they may be on earth. The transnational harassment is conducted by the state’s own diplomats and agents as well as by the “semi-private enforcers,” thugs who are either on the payroll or are simply pro-CCP zealots. And these two forms of international nastiness are only a couple of items on a long list.

As Lind puts it, “The West must cooperate to respond.”