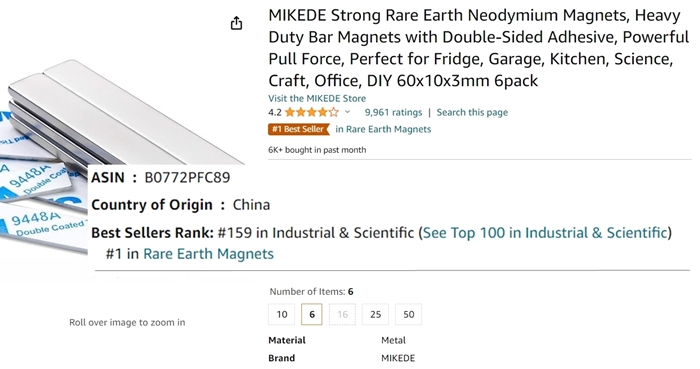

The U.S. Defense Department is trying to subsidize its way into creating a viable alternative supply of crucial military components: rare earths like neodymium, “a silver-white to yellow metallic element of the rare-earth group that is used especially in magnets and lasers.”

China does most of the mining of rare earths and makes most of the world’s rare-earth magnets. Its share of the global magnet market is 92%, reports Jon Emont in a recent Wall Street Journal piece (“America’s War Machine Runs on Rare-Earth Magnets. China Owns That Market,” May 4, 2024).

Trying to decouple

In 2018, the United States “restricted the use of made-in-China magnets in American military equipment, shriveling the list of potential suppliers to a small number in Japan and the West. By 2027, the curbs will extend to magnets made anywhere that contain materials mined or processed in China, covering nearly all of the current global supply.”

But only one U.S. company currently produces the most often used rare-earth magnet. To try to expand the industry, the Defense Department has over the last few years “committed more than $450 million toward rare earths and the magnets they power.”

It’s hard for the American companies to be profitable given the low costs being achieved by the Chinese rare-earth industry, which now dominates even though this industry got its start in the United States and was thriving in the U.S. and Japan in the 1980s.

The first rare-earth magnets were discovered in the 1960s by scientists at a U.S. Air Force laboratory. In the following two decades, military investments led to more-powerful versions capable of maintaining their pull in extremely high and extremely low temperatures….

These magnets were expensive, limiting their applications. In the 1980s, scientists at GM and Sumitomo, a Japanese company, separately invented a new type of rare-earth magnet. They used less-expensive materials but which were so powerful they could attract objects hundreds of times their own weight, improving the torque and efficiency of electrical motors, said John Ormerod, an industry consultant.

By the late 1980s, the U.S. was one of the top producers, second only to Japan. The minerals were mined and processed in California and manufactured into magnets in the Midwest.

So what happened? In the words of engineer Mitchell Spencer, “I built my own gallows.”

A Chinese rare-earth mining boom coupled with lower Asian labor costs eroded U.S. advantages. In 1995, GM divested from Magnequench [GM’s magnet division], which was acquired by an investment group that included a Chinese state-run company. The deal was approved by the U.S. government.

One engineer, Mitchell Spencer, was dispatched to the port city of Tianjin in 1998 to help set up what he was told would be a sister factory to the magnetics plant in Anderson, Ind. Shortly after he returned to Indiana, Magnequench closed the Anderson plant and eventually its entire U.S. manufacturing operations.

People say that hindsight is 20/20, suggesting how easy it is to learn the lessons of history and how nice it would be to know in advance what will later prove to have been an obvious mistake. It’s not quite true that everyone can recognize or wants to recognize the consequences of the worst choices of yesteryear and realizes that we’d be better off if these choices had been avoided. But we should try to have good hindsight; it’s one of the things that helps us have good foresight.

One of the problems encountered by American or Western firms gearing up to make rare-earth magnets is fake local opposition originating in China. This social media campaign has been dubbed Dragonbridge, and the Journal says it was “unexpected.” Maybe we should start expecting made-in-China sabotage?