For centuries, authoritarian regimes have sought to repress their subjects more effectively by adopting tools and techniques used by other authoritarian regimes. They can’t usually get the most up-to-date or insider info from public reports. So sometimes governments consult with each other directly. As Russia and China have done.

We learn from an investigation by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (Daniil Belovodyev, Andrei Soshnikov, and Reid Standish, April 5, 2023) that:

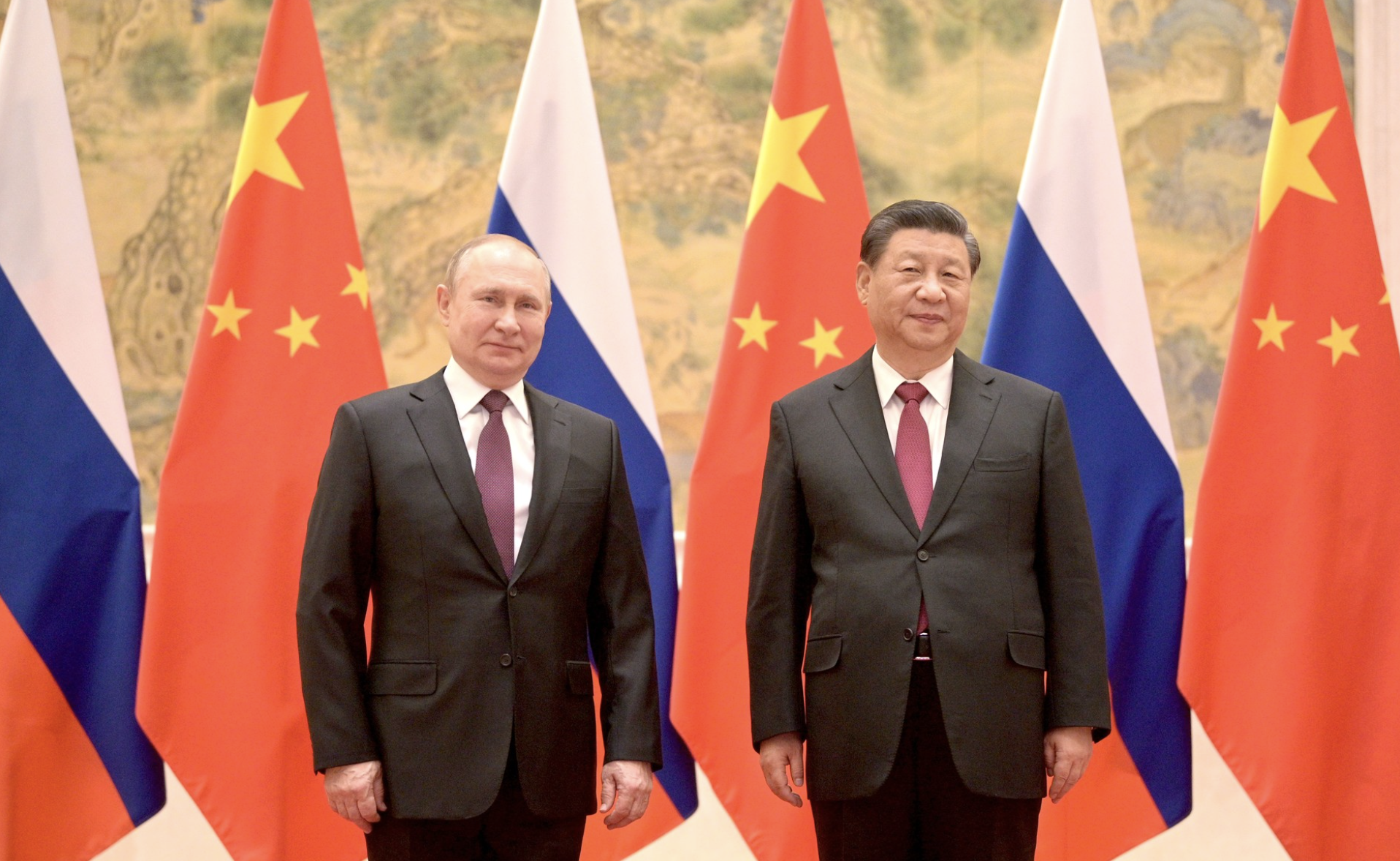

Years before Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin declared a “no-limits” partnership and the Kremlin launched a wide-ranging censorship campaign following its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Beijing and Moscow were sharing methods and tactics for monitoring dissent and controlling the Internet.

That growing cooperation between the two countries is shown in documents and recordings from closed door meetings in 2017 and 2019 between officials from the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), its chief Internet regulator, and Roskomnadzor, the government agency charged with policing Russia’s Internet, that were obtained by RFE/RL’s Russian Investigative Unit (known as Systema) from a source who had access to the materials. DDoSecrets, a group that publishes leaked and hacked documents, provided software to search the files. . . .

Among those deliberations–which are cataloged through meeting notes, audio recordings, written exchanges, and e-mails that have been verified by RFE/RL–Russian officials are seen asking for advice and practical know-how from their Chinese counterparts on a range of topics, including how to disrupt circumvention tools like VPNs and Tor. They are also seeking ways to crack encrypted Internet traffic as well as seeking tips from China’s experience in regulating messaging platforms.

In turn, Chinese officials sought Russian expertise on regulating media and dealing with popular dissent.

The hacked exchanges seem to reveal China as the acknowledged master of online censorship and Russia as the receptive student eager to catch up, hungry for details about the Golden Shield Project and other Chinese advances in pervasive censorship and control.

The authors observe that although Russia is still way behind China in these areas, Russian censorship has become more and more technologically capable and more and more restrictive, “a process that has accelerated since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022.” But both sides have learned from the meetings.

“These high-level exchanges have been going on for some time and they’ve always been focused on understanding what the other side is doing in one area, where they see the other falling short, and what they might learn from each other,” says Andrew Small, a senior fellow at German Marshall Fund’s Indo-Pacific Program. “Internet censorship has been a big part of it because it relates to political stability at home and the shared view that outside forces are meddling from abroad.”