It will take “more than military modernization” to stop China from taking Taiwan by force, argues an Atlantic Council issue brief by Scott Berrier, a retired lieutenant general.

Transformation

The U.S. intelligence community needs the capacity to provide early and comprehensive warning of trouble, which requires a transformation in how intelligence is gathered. This transformation must enable “unprecedented speed and efficiency” and “real-time awareness across all domains—space, cyberspace, sea, land, and air” (“Deterring Chinese aggression takes real-time intelligence,” February 13, 2025).

A conflict with the PRC over Taiwan is neither imminent nor inevitable. The PRC has a strategy for annexing Taiwan without an invasion—and it’s in use right now. This strategy has more to do with cyber power than firepower. But the Joint Force and the IC [intelligence community] must be prepared for all potential futures—including the risk that the PRC might one day try to blockade or invade Taiwan, sparking a global security crisis.

In the unfortunate event of a future crisis or conflict with the PRC, the IC would need to deliver real-time, decision-quality information advantage in all warfighting domains.

The reader probably doesn’t need much convincing about this part of the argument. Instantaneous, efficient, all-integrating intelligence—preferably flawless—about what is happening if and when the PRC switches to full invasion or blockade of Taiwan would be great. How do we get there?

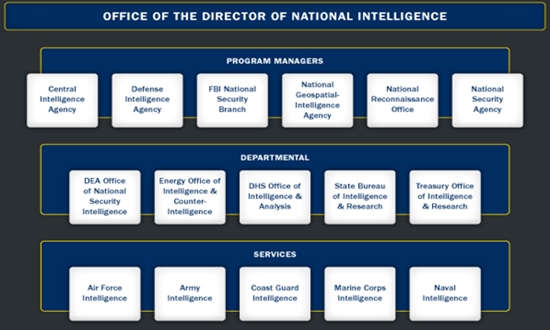

Attaining a real-time, all-domain awareness capability will require a unified effort across the IC, which comprises eighteen independent agencies with authorities to collect, analyze, and report. While some roles and missions overlap, they all have unique capabilities and specified intelligence tasks under Title 50, established laws, and associated IC policy documents. All use different sources, methods, and unique tradecraft to produce intelligence on a variety of national security threats and challenges.

Each agency collects sensitive and restricted information not available to all consumers. Agencies operate on their own top-secret networks and with proprietary software and tools. Each agency partners differently and disseminates intelligence on an as-needed basis (some with more restrictions than others). Each agency has [developed] its culture, governed its own rice bowls, and competed for scarce resources, creating a competitive atmosphere in the IC that limits collaboration and integration.

Transcending this multi-layered segregation of agencies requires presidential leadership. And the cooperation of agencies and Congress.

In a recent, positive development, the undersecretary of defense for intelligence and security (USD-I&S) signed a directive designating the Defense Intelligence Agency as the “enterprise lead” for the common intelligence picture (CIP). This is a good start. But given the enormity of the task, limited time available, and bureaucratic hurdles, DoD will need to go much further—and that won’t happen without a presidential directive, bipartisan congressional support, and a comprehensive approach spanning DoD, the IC, and industry.

Imagine a nationally mandated and funded project to integrate intelligence from all disciplines to gain and maintain real-time, all-domain awareness across multiple networks and classification levels. Turning this idea into reality is the only way the United States and its allies and partners can proactively seize the initiative, reestablish deterrence, and prevail in the event of conflict. To demonstrate US national resolve and potentially advance strategic deterrence, the high-level commitment to intelligence integration and JADC2 [Joint All-Domain Command and Control System] should be highly visible to the PRC and Russia while the sensitive details remain carefully guarded.

A presidential directive focused on realizing JWC/JADC2 [Joint Warfighting Concept/Joint All-Domain Command and Control System] capabilities to address the PRC threat could empower and drive a “whole of DoD and IC” effort to achieve full operating capabilities with strategic impact.

Perhaps, while we’re at it, we can also throw in some jargon-reduction and acronym-reduction to the extent that this is feasible; maybe it isn’t.

Berrier contends that the task he envisions can’t be accomplished “without a presidential directive, bipartisan congressional support, and a comprehensive approach spanning DoD, the IC, and industry.” Let’s assume for the sake of argument that the president and his national defense team see the need for speedy and unified intelligence and that Trump issues the appropriate directives.

Would the effort be futile if conducted only with the support of a congressional majority and not also with the support of the large Democratic minority, so many of whom voted against Trump’s national security nominees? Would it be futile if interagency rivalry and suspicion are only ameliorated, not eliminated?

Deja vu

We’ve been here before, at least once.

After 9/11, agencies having to do with countering terrorist activity were said to be united under the Department of Homeland Security and the Director of National Intelligence. According to an archived Justice Department article published ten years after the events of September 11, 2001, the department had benefited from “a new mindset that values information sharing and prevention, while vigorously protecting civil liberties and privacy interests.”

Well, we must keep trying.